“I guess the news made its way to you by now, John, but I called to let you know the decision in case you didn’t.”

The voice came drumming in a monotone so dry and unpredictable that it belied its seriousness. But John, now listening with his own heart pounding and his own voice momentarily lost, elusive, knew it was crucial. He scratched his head with a nervous finger, wondering why the caller was so calm with news so solemn about something that speared them both emotionally, repeatedly, for close to two decades. Maybe he was just fatigued and had no emotion left.

“Yeah, the Supreme Court ruled today against us in a 5 to 4 vote. I’m real sorry, man, but they overturned everything we worked for.”

The last statement had vestiges of emotion and sounded more like the caller he knew, the words dripping with contempt before the voice waned in defeat and died out so completely that John thought the line had disconnected. But then he stopped listening, anyway.

“John, you there, man?”

“Yeah, I’m here,” he drawled, his own voice husky, hoarse, totally defeated.

“Don’t give up, John, for the fight is not over. What we couldn’t accomplish in the federal courts, we’ll take a shot in the legislature. The fight is definitely not over.”

The voice transformed and reinvigorated, but John detected a hint of surrender. He clutched the tiny cell phone tighter to his ear, straining to hear something more positive, maybe even a reversal, but both men let their silent thoughts scramble inside their overworked minds. John sighed, then muttered, then cursed, his obscenity-laden tirade spurting like a tapped reservoir, bouncing and echoing from the walls of the short, squat building beside him. He tried to sustain what he just heard, the heaviness of his spirit too weighty that he felt his knees shake, his body almost collapse into a heap on the sidewalk. His weary eyes grew damp with dread, disappointment, and he blinked away the tears, then leered into the congenial august air, watching the evening sun wobble and wither then backslide behind a fading sky. Final streams of sunlight flashed across his face, illuminating the coarse lines etched deeply with worry and encircling his eyes and cheeks, curving his lips into an unshakable grimace.

“Yeah, this is really a sorry-ass decision,” his lawyer lamented, emotions embedded in his words. “I really thought they would rule differently; I mean how could they just not see this crazy injustice?”

ohn snarled and watched another sliver of sunlight dribble on the windows of the small building he owned and revamped, glossing over the huge glass, leaving it scorching and sweaty like melting ice. He bought that building not long ago, an old rectangular, two-storied structure with looming display windows, and resurrected and revamped it amid a neighborhood ravaged by crime and the relentless stench of Katrina’s ruins. He got it cheap when it was blighted and abandoned out here in one of those pocket-of-poverty neighborhoods tucked out of sight and away from the gentrified blocks with pristine streets, shimmering cottages and townhouses sprouting balconies and courtyards. He labored on it and loved it, then his toil, sweat, and unswerving hard work blew life into the loins of rotting wood and rancid mold and nursed it in tender care to the glory of its former self. He reveled in the rebirth and named it RAE, short for Resurrection After Exoneration, a new place to nurture old hope from dying years in bondage for John and so many like him, the truly innocent and forcibly damned. This place was more than just a center in the midst of squalor serving released prisoners with job training, advocacy, and a few actual rooms for the newly homeless, but John’s creation and salvation. It was the one thing that went right when everything else deteriorated. RAE was invented as a way to save others from a world that despised them and at the same time give John a sense of accomplishment in a life of brutish, continuous failure.

His life was headed for irrevocable ruins back in 1984 when he was still a petty hustler, street-level drug dealer, and turf punk during turbulent economic times when the actual World’s Fair was in New Orleans and teetering on the brink of disaster, and crime was running rampant everywhere else in the city. Further uptown, on a brisk, cool night the police found the body of hotel executive Ray Liuzza outside his apartment near Josephine and Baronne Streets. Some fiend had slain him during a robbery attempt, lodging five gunshot blasts into his back as neighbors say he pleaded for his life, his shrill voice echoing into the night. A few witnesses shielded by the semi-darkness of their unlit apartments, shrouded by fear, peered into a frightful night and saw a black man fleeing as Ray lay dying in a puddle of his profusely flowing blood.

And back then Orleans Parish Prison (OPP) was teeming with violence and rage when John got carted off the streets and plopped in a dungy, overcrowded cell with over a hundred surly inmates. The tough 22-year old found himself in an even tougher place just watching his already prodigal life spiral further out of control. His overworked mind and dizzying thoughts kept getting stifled by the raucous grumbling and cutting guffaws from a stream of even more harsh men coming in off the streets. These deadbeats, crooks, and criminals tortured him more than the dank musky stench and the sterile, grayish-black walls, their proximity not just abutting him in a cramped space, but their mere presence mirrored his own recklessness. He hated what he saw but he was one of them, another wasted life.

He got blindsided by the arrest and the murder charge, and it marred his consciousness with its unfolding and lurid possibilities, because of all the petty crimes he did, the drug selling and robberies and other stunts that heralded him into juvenile delinquency and thrust him into this wasteland his adult life had become, none included murder. And he wasn’t a carjacker, but that didn’t stop the police and district attorney from charging him with that on top of the murder, loading him with two reviled felonies that made him eligible for the death penalty. And his professed innocence didn’t stop two speedy trials from moving in a maddening succession, and two juries, disgusted with his type, convicting him for the carjacking and subsequent armed robbery and murder of Ray Liuzza. Their disgust transformed to fury then vengeance when they sentenced him to death.

The death penalty. It conjured up images of men burning on aging, wooden electric chairs, their bodies shivering and shaking from the jolts, hair frying like greased meat and smelling like death, and eyes turning red and sultry and popping out before the brain exploded and the body fluids scalded and flooded warm and damp on prison garb. “You are sentenced to death.” Nothing could be uttered with more finality, such rigid assuredness boding into John with dagger-like precision, the actual words more tortuous than the forthcoming physical death. Those words reverberated inside John’s head while he sat stoically in the courtroom’s cell wing awaiting transport back to the parish prison, and even later, as the days, months, and even years unfolded inside the tawdry jail and its hackneyed existence and decrepit moors, a world he despised, he tried desperately to find some way to keep his mind occupied and off his demise. He watched two years elapse after the prosecutors savored a victory and threw him away, and some lying surprise witness testified that he sold a gun, the actual murder weapon, to John on the streets. Two harsh years withered while he rotted in Orleans Parish Prison, a notorious place that grew exponentially over the years.

He peered longingly from barred windows of a drab concrete cell out onto Broad and Tulane avenues, and each time he wanted to yell at nothing, at anyone, at the massive streets divided with manicured neutral grounds, or even the uncurious people walking around used to rants and shouts from that lusterless building that he was innocent and held captive. He was tough enough to survive the violence that raged and swirled around him, shutting out the blood-curling howls from men stabbed in their sleep, and rape victims murmuring and pleading for mercy. He stayed prepared with his own shank nestled inside the coarse mattress on his top bunk and stayed guarded inside this place, an ugly urban warehouse that processed over 70,000 prisoners and arrested people each year, and was known for its special brand of violence so legendary that people on the streets feared ever coming inside even for one night. A massive, hulking string of buildings, OPP wasn’t a whole unit but various jail and prisons with names like the Intake Processing Center, Temple man Jails I, II, and III; the House of Detention; Old Parish Prison, and the Community Correctional Center, all overtaking nearly three city blocks.

The first two brutalizing years in OPP hell got more rugged the summer of 1987 when tempers inflamed and the viscous heat of the Deep South, burning and blazing, infiltrated the concrete- surrounded cells and intensified like a broiler. But worse than the hellish dawns John woke into each morning amid the chaos and confusion, the executions out at Angola started moving at a rapid pace, eight men put to death in the span of eleven weeks. The rapid executions made the headlines in New Orleans, plastered in newspapers and blasting from the wire-meshed television set tucked in the upper corner on the tiers at OPP. The words, “I sentence you to death,” uttered in the courtroom now were more definite, echoed and more pronounced years after they were pounded deep into John’s consciousness. Death had a new stunning reality; men at Angola saw assembly-line style executions with almost one per day and John was thrust into this especially cruel reality. Death row inmates definitely died.

And that month he got jerked off the tier and transferred to a world beyond sheer confinement, a place that was the prelude to death, so reviled that he wasn’t even good enough to be around the rapists, thieves and even other killers. They bused him and others out to Angola, an 18,000-acre prison farm where legions of inmates worked in the fields, but not him and the other most hated men in Louisiana. No, they got their on special one-man cells, miles away from anything that even resembled humanity, the last steps before the death chamber, the chair, and the grave. He was another throwaway, sealed, packaged and prepared for incineration in Ole Sparky, confined for 23 hours a day with just an hour to walk the tier and think about dying.

John’s life dragged on like that for years, a despicable routine of isolation and utter loneliness in an insulated cell and the paradox of being a sole occupant in a place, the tier, with continuous, cacophonous eruption of raging voices that never ceased, never slept. So cumbersome, those voices, the callous laughter and cussing, the shadowy images of guffawing criminals that crept into his dreams, transforming them into nightmares then jutting him into wakefulness just to face the repeated uproar. Ironically, it was the shadowy images that became actual persons in the day, angry and obscene rejects from all over Louisiana that would be a bit of his salvation. They were brutes, but he could occupy his time by talking to them, listening to stories of mayhem, murder, and total madness, but therein lied the paradox. The stirring accounts in the astonishing first-person, spoken with a range of colorful, divergent emotions actually eased time. It had its own weird way of soothing him.

And he needed aversions in a world where time stopped, stood still, immobile, so cruelly unmoving that the days of the week got jumbled and indistinguishable, the hours of the day so tediously routine that he could predict every moving moment and touch each inexhaustible minute. He heard the creaking wheels of supper carts inside his head before they even came rolling humbly to a hungry tier ; he listened intently to the snort and grumble from the COs before they crept the hallways for roll call, or when they came grim-faced baring the death warrant with the actual time to die. The voices from the rest of the damned helped, their own stories horrific and disheartening like his own, and he listened out of sheer boredom and tedium then cried inside, especially when he heard those pleas of innocence ringing like dirges. Men like him pleading to other men who couldn’t help. Men like Shareef Cousin, barely a man, a man-child burst out of adolescence into a gangly sixteen-year-old with dark, searching eyes and thick, unkempt hair matted and wiry on top of a sullen, confused face.

When the COs led the youth to his cell, contiguous to John’s, he felt a sensation that there was something amiss, weird even, and inexplicable about his neighbor. He had been out here in nothingness waiting to die for a decade when the youth got dropped off next to him, and later when he got the pittance hour of time out of his own cell, he stood before the thick bars and peered at his neighbor, stunned by how young he really looked.

“I ain’t done this crime, bruh,” the new cellmate uttered, the words deliberate and passion-packed, his unwavering, unblinking eyes dark yet bright like dying embers. “I didn’t kill nobody, man. I wasn’t even around when they shot that man. They got me down bad, bruh.”

That utterance, eerie in its depth, usual in its plea and morbid familiarity, made John backslide a couple of steps, his own face suddenly dark and downcast, eyes deep and locked on the youth. He looked closely at Shareef’s dark chiseled face, smooth and jutted like a leather-textured stone, and saw something bewildering in those roving, beseeching eyes that engaged and rejected at the same time. He saw himself, ten years ago, pleading and swearing innocence while squirming in anguish inside an empty cell. This gangly teenager standing over six feet and shifting his feet nervously gave John a nasty dose of Déjà vu, as though he departed his body and his soul suspended from the air and watched the reenactment of his own life.

Just like John, Shareef was convicted of murder and armed robbery and shoved a death sentence. And resembling John’s turbulent youth, Shareef was young, black, and completely despised by the D.A’s folks down in New Orleans. And strikingly like his own case, Shareef was arrested for killing a white man, a decent respectable citizen who had no reason to die and absolutely everything to live for. John’s alleged victim was murdered ten years ago in Uptown New Orleans; Shareef’s was on the edge of the French Quarter, gunned down by some vicious thug a few feet from his fiancée. Their similar cases bonded them and cemented a brotherhood of wrongfully convicted men who had the audacity to get into trouble down in New Orleans.

Before Shareef came along and gave John a neighbor to talk to all the time, he suffered in hell. Not the biblical fire and brimstone hell, but this man-made inferno of unceasingly angry men and dizzying thoughts that poked holes and ate at his sanity. And further away two angels left heaven for the city of brotherly love in the far northeast. Philadelphia, the old city, the bold frontier and once “promised land” that sprouted the first American society dedicated to the cause of abolition in 1775. Not exactly 1700s Quakers bursting the shackles of slavery, two new-age lawyers, Gordon Cooney and Michael Banks, both partners at the prestigious Morgan Lewis Law Firm, both brilliant and unflinchingly loyal to justice decided to take a life-altering pro bono case that contained a possible innocent man wallowing down in Angola.

Maybe they were the Quakers of old, renewed and reinvented and raring to fight until the end. It was always the benevolence of the north extricating from slavery men mired in the wicked antebellum south, and now, over 140 years later, these two northerners, elite prep school graduates wielding Ivy League degrees and impressive legal acumen, worked to free a man from bondage in the deep, unmerciful southern bayous of Louisiana. Things changed rapidly over a century and a half but in other astonishing ways remained the same. Yep, Cooney and Banks definitely showed signs of Quakerism from the old days flowing in their personalities. And when they met John out at Angola in the puny visiting booth surrounded by cinderblock walls and attentive COs in staunch black uniforms, they immediately felt compassion for the bedraggled man, helplessly downcast yet with a sterling sparkle of fight still left in his harsh eyes. He was young like them, but socially, educationally and economically a complete cosmos away and he was one of those glaring, grim statistics: black, urban, and buried deep in incarceration.

They had never been to a place like this, lodged deep down near the river, a three-tiered cellblock where people waited to die. No, this is where outcasts went to after a lifetime of dreary days, heartbreak, and leaving a violent mark on some city they got snatched away from. No doubt most of them deserved it, especially for the heinous shit they did to people and property, but nobody, absolutely not even the lowest of the low deserved to die. And the state shouldn’t be in the business of killing its citizens. The privileged upbringings, the safe clean neighborhoods, great schools that cost a fortune and both of them born the sons of prominent lawyers, didn’t weaken their sense of sympathy for the poor, or this case the truly downtrodden and detested. In fact, they weren’t so sure John was innocent but they knew they didn’t want the beaten man to die.

But Louisiana is a strange place with its own unique politics and law and even bizarre ways of carrying it out that two northern attorneys never got training in law school. And they couldn’t imagine taking on the powerful D.A., Harry Connick Sr., a man with a name so recognizable and influential that his nephew, Paul Connick, ran the neighboring Jefferson Parish D.A.s Office, both men sharing prosecutors who moved about the two offices interchangeably throughout their careers. They couldn’t fathom courtrooms in both Orleans and Jefferson parish that sent a heap of offenders to the jails and penitentiaries, meting out some of the longest sentences in the nation, with D.A.s so proud of the death penalty that they awarded prosecutors who racked up the most convictions. Over in Jefferson Parish, prosecutors even wore neckties with the emblem of a noose in the actual courtroom when they took a shot for the death penalty, and then there was the proud prick award, a plaque with a hypodermic needle placed over the office door of the winner of convictions. The old southern boys down in Louisiana were blatant with pride in dispensing death to those thugs from New Orleans and its suburbs.

And no fool lawyer would take on the Connicks and expect to make it in the closed, cliquish legal world where everybody knew each other and careers could get derailed with a phone call. The local lawyers, the good ones anyway, stayed away from Thompson, Cousin and others like him, and the poor ones from Legal Aid just didn’t have the time, resources, or experience to mount a good defense let alone an effective appeal. They walked away from the case after the death sentence tumbled from the bench and crawled back to their overworked cubicles. And that was it. They wouldn’t dare fuck with a man like Connick if they wanted to become anything else worthwhile in that city. The man ran the D.A.s office for well over two decades, and judges, corporate lawyers and other big shots got their start there, enabling the big man to have contacts all over the place. The owed him favors and he definitely cashed in when he needed to. He could squash your ass like a bug if you messed with him or his business.

Cooney and Banks learned that quickly, the outsiders, northern sympathizers, realizing things were done differently down south. Every appeal strategy they used got rejected one way and thrown out with hostility the other. Nobody liked them and not one sympathetic judge wanted to hear them; they essentially got kicked out of the courthouses with a nonverbal cue to haul it back to Philly and stay out of Louisiana’s business. Go back to the lofty law firm up on the east coast before you get yourselves into some trouble down here. And so, with that finality and defeat, they met with John in the dank visiting booth on death row, feeling like failures for the first time, losing and hating every bit of it, and now forced to tell a man he would die after all of the time and hoping and mountains of paperwork filed on his behalf just to have some judges piss on it.

It was lukewarm and sunny, a vibrant wind sauntering off the bayou and rattling it until it wrinkled and lulled, all of the water around the prison so pristine and calm that it belied the stuffy visitor’s booth and suffocating thoughts the two lawyers and their clients underwent just a few feet away on death row. It was April of 1999 and John had been backlogged inside his cell here for nearly thirteen years, and now, death was an absolute, and the two brave white men from the north couldn’t save him and even admitted it. He was going to the gurney after the lawyers lost thousands of billable hours on him and they had to head back to their old jobs of corporate work and simple, upper-class lives in the suburbs. At least the electric chair was gone. They didn’t burn people to death out here with mismanagement and faulty wiring, but they pumped them with poison and they died just the same. Your body just didn’t have those disfiguring burn marks and ugly lacerations and was more presentable for an open casket funeral but you were dead nonetheless and your death sustained the humiliation of being killed for not being a decent member of society.

When the lawyers left that day, John lay on his brittle bunk and couldn’t shake away those hopeless expressions, how they appeared so utterly defeated. They used to be two towers of strength here in this forbidden zone, always smiling and joking and talking with impeccable optimism about getting the courts to reverse his sentence. But today they looked more like doctors telling their patient the cancerous tumors spread, or the pathetic court-appointed lawyer frowning when he lost the case he couldn’t win anyway. And in that defeat, John saw how genuine these men were, how they really wanted to help him, and now they felt like losers when he was the one actually going to die. And they left him back to his loneliness, now more profound and terrifying because there was nothing to hope for. He survived seven stays of execution over the years, but now the death warrant dropped off in his cell by a classification officer had the final, non-negotiable date and time of his execution.

He couldn’t complain to Shareef, who had his sentence overturned and escaped the rigors of death row. Some journalists from Time Magazine came out and interviewed Shareef a few years ago, ran an in-depth story entitled Dead Teen Walking and exposed prosecutorial misconduct in the Orleans Parish D.A.’s Office. It was some shockingly revealing stuff in the cover story, and it got the higher courts to throw out the death penalty conviction and got the youngest person on death row free. Well, not completely free; his charges for unrelated armed robbery stuck and at least he got transferred into the general prison population. He walked among other armed robbers, carjackers, thieves and liars, but he had his life and the end of the sentence meant freedom. John groaned at the irony of getting so close to Shareef, a youth who went to school with his own son, then suffering when he got unshackled and released. The picture in Time Magazine of his dark face peering behind bars under the powerful captions that would free him, that stark image, motivated John to keep believing, pushing. A powerful magazine stated that there were dirty prosecutors in this world and they framed innocent black men. Powerful people read powerful magazines.

When John resigned himself to the execution, frustrated that it was scheduled for the same day as his son’s graduation from high school, something miraculous burst through the bayous and brought him a special phone call from his lawyers. He listened to his lawyer, noting the high-pitched tone, the celebratory way his voice labored like it couldn’t stop. And he blurted the news: his private investigator found a crime lab report with tests performed on a piece of pants leg and tennis shoe that got stained with the perpetrator’s blood. The lab report indicated that the perpetrator had Type “B” blood and John had Type “O” blood, proving he didn’t commit the carjacking. The prosecutors played dirty and set him up on the robbery; they had scientific proof that he wasn’t the robber.

“Man, you serious?” John heard his own voice crack, his mind so transfixed that he stopped hearing the routine barbaric cussing, fussing, and senseless noise permeating the tier, swarming around his head.

“Quite serious, John. Quite fucking serious. And the P.I. is digging deeper, searching that property room on Broad Street meticulously. We’ll see what else we find, but I know we can get that armed robbery charge thrown out with this.”

John tried to imagine the evidence, the bags of old clothes, a tiny microfiche with blood spots, tennis shoes splattered with blood, someone else’s blood. But it wasn’t hard to see the cold, hate-filled faces of those prosecutors, the way they glared at him in the courtrooms, sometimes snarling and even snickering, and other times just slapping him with stony stares and unblinking eyes, as he got dragged away in handcuffs and shackles like an animal. He couldn’t shake those images even if he wanted to for they boded and tortured him for over fourteen years, and he hated them, the ghouls rousting him from his sleep, and the real cruel men behind them never leaving his mind while he was awake. And now within days of his death, something he always knew was creeping out, little bits and chunks of evil schemes and scandals helping the conviction slowly fall apart. If they found this, was there more? There fucking had to be because he was innocent.

And there was a hell of a lot more. John’s second jubilant call from his lawyers resounded with such a thrust that it stifled the voices a few feet away inside the massive cellblock, the message exploding inside his head. He felt his lawyer’s optimism, unbridled and uncontained, over hundreds of miles away from this bayou country, out in New Orleans where they hadn’t packed for Philadelphia yet. The resourceful P.I. they hired, a sexy, savvy, intuitive type with brains and beauty, wooed her way into that property room under the horny nose of some overworked cop and found over thirteen additional pieces of evidence that never made it to the defense all of those years ago. And this evidence, more startling than the blood evidence, pointed directly to the murder that he didn’t commit, proof, scientific and loaded with proven alibis that stayed buried while he rotted on death row.

Crucial evidence, like witness statements in police reports identifying the killer as “ six-feet-two” with a “ close-cropped” haircut when everybody else in the world knew John was a short five-feet- seven with a large, wiry afro. The lying informant actually got reward money from the victim’s rich family, somehow convincing those grieving folks that John was the killer, and the jury never heard about it. There was so much more, so astounding and revealing that John found himself in a daze when a group of CO’s approached his cell and told him to “get ready to go.” While he looked at them quizzically, thinking everything he heard the last few days were hallucinations, that he was headed to the death chamber, they glanced at each other, then an expression crossed one of their faces and he actually smiled reflexively.

“You’re not going to the death chamber, Thompson,” he grumbled in his thick Cajun accent, his finger jutting for emphasis. “You’re going back to New Orleans, man, to OPP. All this shit got thrown out; you got a new trial back in New Orleans.”

He stood for a moment watching John closely, all eyes locked on him, all voices and sounds and even just the whimper or air that courses weakly through the tier surrendered to a reverential silence. For a moment the entire world was still.

“Good luck in N’wlans, man,” one of them said, his unsmiling face filled with sincerity. “Good luck with those low-down bastards.”

After almost eighteen years of suffering and soliloquy in a lone cell, John got escorted by CO’s in the long drive out of the bumpy Tunica Hills, his mind getting pummeled with thoughts as the DOC van traversed roads and highways amid sparkling bayous and magnificent forests teeming with game. He was going back to New Orleans, to OPP, to the place where his end had a beginning and his past was being thrust into the present, to that archaic prison that stood so dark and sullen in a neighborhood, dominating the night and dragging its doldrums into the mornings. He had to go back to that place and ready himself for the fight of his life, his final chance at freedom.

The city looked essentially the same, John thought as he gazed from the van’s small windows as they barreled on I-10 East through suburban Kenner. Still wide and massive with malls and businesses dotting the outskirts of the highway, it had that charmless character and rigid ordinariness in a sense that it was a simple place to live and work and nothing else. National chain restaurants tucked away near modular malls, houses sitting low and nondescript, everything insulated and nothing ostentatious or eye-catching. It all looked that way when John got dragged out of the city back in 1985, but its biggest transformation was the Connick’s encroachment all the way out here to the suburbs. Paul Connick became the D.A. while John was locked up, and for a while both nephew and uncle had a monopoly on locking the key and throwing away those wayward criminals from the huge Orleans and Jefferson Parish.

Harry Connick Sr., the man whose office destroyed John’s life, was finally out of office but not likely out of power. He pulled that office from the legendary Jim “Big Jim” Garrison back in 1973 and reigned for 29 years, finally stepping down in 2002. He was omnipresent, resilient; the ultimate city politician who had built solid relationships with black politicians and musicians that gave him longevity with the minority community that topped at 70%, mainly African American. For a white man in a black city with an office with some of the worse Brady violations in the nation, he managed to hang on, winning re-elections, even when the Federal courts disciplined him for not turning over evidence in cases primarily involving African American defendants. He smooched with the best and brightest politicians and city leaders, even the mayor, who endorsed him, and as a balladeer, crooning at nightclubs in the French Quarter, he created an untenable friendship with the black musicians, hundreds of them spouting trombones and tubas and clarinets and supporting their tough-on-crime D.A. It took nearly three decades for him to decide to step down but not out, his huge presence and spirit always lurking the halls of old courthouse.

But he wasn’t prosecuting John again; Eddie Jordan, the first African American D.A. was, and the avalanche of new evidence, once buried and thought irrecoverable, came surging into the courts. John’s lawyers even brought on a local criminal defense lawyer to help them with his retrial and the peculiarities of a Louisiana court, and after hurried and excited preparations for weeks, the murder trial of Ray Luizza got underway again, eighteen years after his death. A newly seated jury heard the impassioned arguments, scanned the amazing array of evidence, and once impaneled to decide John’s fate, took about ten minutes to pour coffee and pick out Danish, slurp and nibble, and decide in a record twenty-five minutes that John was innocent. Thirty-five minutes and John’s freedom was granted; the jury found him resoundingly, absolutely not guilty of first-degree murder. The killer of Ray Luizza walked the streets for nearly two decades, mainly because nobody was looking for him.

On a warm day in May, burgeoning quickly into tropical Louisiana heat, John walked out of the tortuous OPP a free man. It was 2003, and after almost 19 years in OPP and death row, the humid, fresh air of freedom washed across his broadly smiling face and the media cameras flickering in frenzy and a coating of the sultry sun cast his weary body in an almost ethereal glow. He was free from the relentlessly impending death dates, the pitifully lone cell with screaming voices on the outskirts, but a knew kind of psychological torture awaited a man who had been pulled from society and buried deep in the wooded parishes of Louisiana. He left the prison world with a small bag of tawdry eighteen-year old possessions and $10 for bus fare, the standard, stingy crap they gave exiting inmates.

But John wasn’t a lone man coming home from captivity; an influx of nearly 15,000 released inmates shook off shackles and chains and headed back to New Orleans and Jefferson Parish. John was thrust into that disillusioned bunch of largely uneducated, jobless men who were starving for those limited social services back home, but unlike them, he was innocent. And that created a predicament of being free to leave prison but not eligible for the scant services and post-prison re-entry programs because he wasn’t an official parolee. He was a newly coined exoneree, innocent now free but still burdened with the stain and stench of the penitentiary and no social structure to re-integrate him into society. He was much worse off than those thousands of parolees trotting back to the city with dazed eyes and weary feet. The way the employers see it: innocent or not, you were still shackled, hobbling in misery on some prison farm heated with violence and helping you get an unhealthy dose of jailhouse values. We couldn’t possibly have you in our company contaminating the place, could we?

He hated the unwelcoming free society as much as it hated him, but he saved a prodigious contempt for those prosecutors who destroyed his life and went on comfortably with theirs. There was Gerry Deegan who supposedly confessed to Michael Reihlmann back in April of 1994 that he suppressed John’s crime lab report. They met at one of those local bars near the courthouse where lawyers booze it up to celebrate a conviction or lament a dirty criminal winning acquittal from a stupid jury, the kind of place where Deagan knew his confession was safe. He was suffering from liver cancer then and facing his own mortality, so he told Reihlmann instead of going to some confessional and risking a priest forsaking his vow and turning on him. He didn’t want to go to jail before the cancer killed him, and he may have been warning Reihlmann in case some scandal broke out, somehow that missing evidence reappeared. He died three months later, in July of 1994, but Reihlmann kept his secret, scoffing at the Brady Law like it wasn’t shit. In fact, Reihlmann didn’t come forward until years later, in 1999 around the same time that P.I. working the Thompson case found the hidden crime lab report.

“His ass came running to confess, because he knew we found out what he did,” John surmised, assertively, snorting at Reihlmann’s claimed need to do the right thing. “If he was so right, then why he took all of those years when he knew I was innocent. He ain’t had a choice. That ain’t no coincidence he came forward the same time we found out they was hiding shit.”

Deagan escaped the scandal by dying years earlier, but Reihlmann became the first and only prosecutor in the case to have formal charges filed against him by the Office of Disciplinary Counsel (ODC). Those officials pointedly wanted to know why he didn’t report Deagan’s disclosure, and in a sworn statement he explained: “I think under ordinary circumstances, I would have. This was unquestionably the most difficult time of my life. Gerry, who was like a brother to me, was dying. I’d also left my wife just a few months before with three kids, and was under the care of a psychiatrist, taking antidepressants. I would have reported it immediately had I been in a better frame of mind.”

The Supreme Court of Louisiana didn’t really like that excuse, and on January 19, 2005, publicly reprimanded him. They were merciful, not bludgeoning his career with disbarment, but suspending his law license for a few months. John didn’t especially like that wimpy slap-on-the-wrist punishment, but then the others got away without even a scolding. And there were others; he remembered them all in that courthouse hovering about the counsel’s table, plotting to destroy him. None stood out more than Jim Williams, a tenacious D.A. lieutenant back in the 80s and 90s who touted prosecuting by 2001 one-eight of Angola’s death row. He has been featured in Esquire Magazine and other magazines and books about his death penalty conviction prowess with juries in criminal trials, all at a time when D.A. Harry Connick proudly stated, “We need the death penalty to show life is precious.”

There is a picture of Williams in that Esquire article back in the 90s, an imposing figure standing resolutely before his desk, his face pasty and solemn, not even a vestige of a smile on his thin, tightly shut lips. A natty, dapper man in business apparel one would associate with a successful CEO, he was, paradoxically, a corporate type but his corporation was the desolate and dusty courtrooms and meandering hallways on Tulane and Broad and his product was death. That’s what he was selling and he was meeting his quota. He stares at the camera through horn-rimmed glasses, his gaze deadly serious and even intimidating, probably the way he glared at his defendants in the courtrooms in New Orleans. It is inarguably a death stare, uncompromising and unapologetic, a harbinger of the convictions that he would render from the juries down south several times. He revels in sending men to death row.

“If anything makes me mad about these abolitionist appellate lawyers,” he said to a writer, “It’s how they keep these guys alive for eleven years, average, at huge expense, then talk about how all that time on the Row constitutes cruel and unusual. The manipulation of the law doesn’t bother me. It’s the moralizing the pungency they argue the position with.”

In that same stark, black-and- white photo of him in Esquire, there is on his desk a tiny replica Angola’s electric chair. Pasted to its seat are cutouts of the faces of the men he’s condemned. John’s picture is in the center. He hates Jim Williams more than the actual gurney the state wanted to strap him to.

“That man got away with so much,” John laments, his voice filling with wrath when he talked to me in New Orleans. He pauses as a swath of anger passes, intense and cumbersome, a writhing, swirling emotion that assailed him for eighteen years.

“That man put all of us on death row, is proud of it, and you know them prosecutors knew we were innocent. You now, all of the men on that picture in that tiny electric chair had those convictions overturned since that stuff got published? Yeah, and most of it was for prosecutorial misconduct, but nothing happened to him. Justice was not done, man. Him and the rest of them prosecutors out there working in their field, you know, making money and look how they ruined our lives. It ain’t right.”

Cooney and Banks, now almost two decades defending John and becoming close to him, agreed that justice wasn’t served and they needed to dig deeper and make it work, the way it’s supposed to. Even for a man like John, an angry black man once with frightening photos plastered on newspapers, making him easy to despise, deserved justice. And so, with the backing of their illustrious law office in Philadelphia, the two men filed a lawsuit against the District Attorney’s Office of Orleans Parish. John was elated to take a swing at the system that ruined him, and suing those cutthroat prosecutors that actually thought they evaded chastisement gave him a mocking sense of vengeance. That he was able to do something about what happened after the tragedy gave him hope, that precious emotion that sustained him through his worse days and made him growl mightily today.

But a lawsuit against a powerful local government agency, run for decades by an even more powerful politician, was a formidable challenge and the two lawyers didn’t go at it expecting a quick, easy win. And then a major hurdle would be dodging Imbler v. Pachtman, a United States Supreme Court ruling back in 1976 that gave prosecutors complete immunity from civil liability, making them untouchable, irrespective of how egregious the misconduct was. The Court in its infinite wisdom felt it was okay to deprive a wronged defendant of civil redress to avoid the alternative of prosecutors becoming timid and fearful of making mistakes that could leave them penniless. John’s lawyers had to be clever and craft a way around Imbler to at least get the case into court, get it past the stern eye of some tough judge and make its way to a jury, twelve people who could identify with a man being derailed and ruined and seeking damages. Who wouldn’t sue if their father, brother, son, or male friend got locked up for nothing while some grinning prosecutors strutted around like nothing happened? They had a chance if they got twelve people thinking like that, if the judge wouldn’t cite Imbler and throw the case out.

To avoid Imbler altogether, they took a different route using creative strategy and attacking the D.A. in the lawsuit from another angle. The theory of municipal liability was the way to go; the claim that gross incompetence caused the D.A. to violate its contract with the community and led to a man’s constitutional rights being trampled and his horrifying, continuous near-death years irreversible. Their lawsuit would claim the D.A. failed to properly train and supervise his staff, especially on Brady, that core law that requires prosecutors to turn over exculpatory evidence to the defense. And Brady, which originated out another Supreme Court case, Brady v. Maryland in 1976, was definitely violated here, and further research revealed that Connick’s office had a sizable number of similar violations over the years. They would have to steer away from the accusation that prosecutors were illegal hooligans who hid evidence out of sheer malice, meaning they were aware of Brady and chose to ignore it, and instead shoot for a case of dummies who wouldn’t know Brady if it slapped them in the faces. And it was the only shot they had to even get the case moving through the courts.

John waited and hoped and found new struggles in a hostile world that didn’t want ex-offenders, or exonerees, or whatever they were calling themselves these days, anywhere around solid citizens. He got the customary nod of sympathy from human resource professionals who shook his hand then shredded his application before he made his way out of downtown. Sure, he was innocent and wronged and all of that and some employers understood his dilemma, but he was tainted with an unshakable, perceived reputation originating from a modern day barbaric land and they couldn’t trust him around others. His mind was likely screwed up after prison and death row, and all of that other rape and savagery, and they couldn’t take a risk, hire him and take on a lawsuit if he maimed or killed somebody at work.

One really pitying small business owner, shaking his head wearily while clutching John’s application in the other in an overworked hand, just blurted the truth, in its coldness and realism, his own voice helpless and almost beseeching, “You know I really wanna hire you, John. But my insurance provider will drop coverage if I hire ex-offenders. I know you’re innocent and all, but I don’t think that makes a difference to my insurer, you see.”

John met someone, a strong southern woman with tidy New Orleans ways, and married her shortly after. And he found work, first as a legal assistant for a church then as an investigator on death row cases for a law firm, bringing him out of the wilderness of uncertainty and into a more secure life of employment after being off the payrolls for nearly 20 years. And he reconnected with Shareef Cousin, his death row neighbor, now free and redefining his own life in the city, and the two concocted a plan to start a program to help men like themselves: wrongfully convicted, freed, and forced to fend for themselves without an iota of compensation from the governments that destroyed them. It was actually during those long, bitterly lonely nights on death row that they conceived finding a way to aid men and women like themselves, right before Shareef got sprung and John started hoping that he might secure his own freedom. And now, both free, idealistic but still bitter, they found a way to make that idea become a reality with John’s new employer, The Innocence Project New Orleans Office, lending him office space, a small anterior room in an old building downtown. He became executive director of RAE and Shareef came aboard as his assistant director of this fledging organization with hefty promise, the hopes and dreams of hundreds of the accursed lurking in its dusty corridors leading to the small office.

It got a blessing and seed money in the form of a $60,000 grant from a New York foundation and a $200,000 pledge from a donor in Europe, pushing RAE out of infancy dream into a vital, soon-to-be functioning institution, and the sudden deluge of great things moved about unabated when John won a $14 million judgment against the Orleans Parish District Attorney’s Office. RAE was real and help was coming to those other exonerees unlucky enough to have gotten ensnared, hope riding on the winds of a once totally desperate landscape. And the newly appointed D.A., Leon Cannizaro, a former judge, inherited a windfall of financial problems from his predecessors that could easily push his office into fiscal chaos, possibly bankruptcy. Eddie Jordan, the D.A. forced out of office by a furious electorate, left Cannizaro with a $3.7 million hole after paying that amount to plaintiffs in a lawsuit where he fired 43 white employees who worked under Connick and replaced them with black workers. He fought it when it was just $1.9 million, but lost under appeal and had to come up with the $3.7 millions the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals said he owed the aggrieved employees.

John’s $14 million judgment came right on the heels of the big payout and forced Cannizaro into a corner, giving the new D.A. little choice but to fight to protect the taxpayers money, even if he personally had nothing to do with misconduct, incompetence, sloppy administrative decisions, and other foolhardy acts occurring in that office. His office couldn’t pay a judgment that surpassed the size of his budget, so he ran to the 5th Circuit and dropped off a hastily prepared appeal and prayed for delays and a reversal while he tried to figure out this mess his now departed colleagues dragged him into. And while RAE was growing and John was speaking out against the evils of the D.A.s on radio and television, the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals sent to Cannizaro’s office a formal decision stamped with imposing federal letterhead and delivered by a court courier. The three-judge panel was unanimous; the lower court decision should stand. Thompson still had his $14 million payable at any time.

Fearing bankruptcy as the only way out, Cannizaro went back and begged the full sixteen-judge panel of the 5th Circuit to hear the case, and they did, pulling John further away from his millions and the victory he had already earned. And they returned with a verdict, not that long after, a stunning split down the middle, eight supporting the lower court’s decision, eight others ruling for a reversal. As it works in big 16 judge panel cases, an evenly divided court means a victory for John, although a close call. He knew now that 8 judges out there ruled against him, and only one feisty jurist could have decided not to support them and would have overturned all of the work his lawyers did and snatch away $14 million for now still hanging in midair. One of the dissenters, Chief Judge Edith Jones, wrote: “Today’s judgment raised issues that will continue to plague honest prosecutors’ offices.” That pleased Cannizaro immensely, and emboldened by the fact that there were definitely judges who would take his side against the judgment, he appealed to the United States Supreme Court.

Cooney and Banks knew that the high courts only agreed to hear 1% of the cases submitted, so coupled with their three victories so far they felt confident the case would be refused, and they could get to work collecting John’s money and even paying back their own law firm the millions it had already spent over two decades on this case. To their consternation, the high court decided to hear the case in the spring of 2011. John’s fate and settlement now depended on the most conservative court in the land, with millions at stake and the thousands of other wrongfully condemned waiting and cheering from the sidelines. If he won, and he prayed that he would, his lawyers would have found a way to virtually overthrow, or a least work around, Imbler and open the floodgates to litigation from all of those other exonorees, the ones appearing on television so tedious and defeated that their voices cracked and whimpered and their eyes stayed downcast even in freedom.

The district attorney’s office didn’t contest that its prosecutors withheld a crime lab report favorable to John, but it emphasized the fact that prosecutors ordinarily couldn’t be sued for their official actions, almost citing Imbler verbatim, their only chance to beat this thing and get out of looming $14 million debt, which with interest had grown past $15 million. That, in essence, was their defense, and it was bolstered by the fact that the high court just a year before ruled that a California man who spent 24 years in prison on a wrongful conviction couldn’t sue the former Los Angeles district attorney. The case was risky and John, having survived seven stays of execution, yearly severe isolation and humiliation, waiting to die, wishing death then pleading for life, his voice hollow and helpless, found himself once again in a critical fight to redeem himself, make his life whole and meaningful. Waiting for the Supreme Court’s decision was crueler and inhumane punishment for a man who did nothing other than dared to be poor, black, and male on the rugged streets of New Orleans.

Talking to the media anytime he could, lamenting his plight even though he knew his lawyers were preparing an astonishing argument for the high court after twenty years experience, he said acceptance of the appeal “ represents yet another delay in the process of seeking justice that has, for me, been going on since I was arrested in 1985.”

It was much later than 1985, 2011 to be exact and now approaching the moist air of spring, with shards of sunlight soothing the city the color of tangerine. And John by now grew RAE from a bungling, cluttered office back on Chartres Street in the rear of the French Quarter to a fortifying agency to care for newly freed, totally lost and bewildered returning exonerees and ex-offenders. He got funding to rehabilitate an old building rotting in the ruins of the 7th Ward and transformed it into a halfway house, providing living quarters for a small few and job-readiness workshops and other survival meetings for so many others. Shareef has moved on to Atlanta to work as a legal clerk at the Southern Center for Human Rights and attend Morehouse College.

“I remain confident,” John said in bouts between his dizzying schedule or running a halfway house and keeping RAE visible and active, “that in the end, prosecutors who sent me to death row for a crime I didn’t commit will be held responsible for their actions.”

John held the cell phone to his heart, pressing it with his might, trying to squeeze out the reality of the message he heard. He stood out on the sidewalk for what felt like hours but was only about a few minutes, his face darkening as evening abated and nightfall crept through the crevices of the sky. He dealt with disappointments before, a slew of them, constant rejection of appeals, one stay of execution after the other, making death still there and menacing in the shadows, but this one had a hardened finality to it, that point of no return that left you in astonishing disarray of not knowing what to do next. And this new disappointment, Connick v. Thompson, 09-571, that came crashing from Washington D.C. in the breezy month of October, left him absolutely in a new kind of anguish. In a 5 to 4 decision, in a bitterly divided court along ideological lines with conservative justices against the judgment and liberals staunchly in support, the millions that he never saw, never touched, vanished as quickly as a creaking wind.

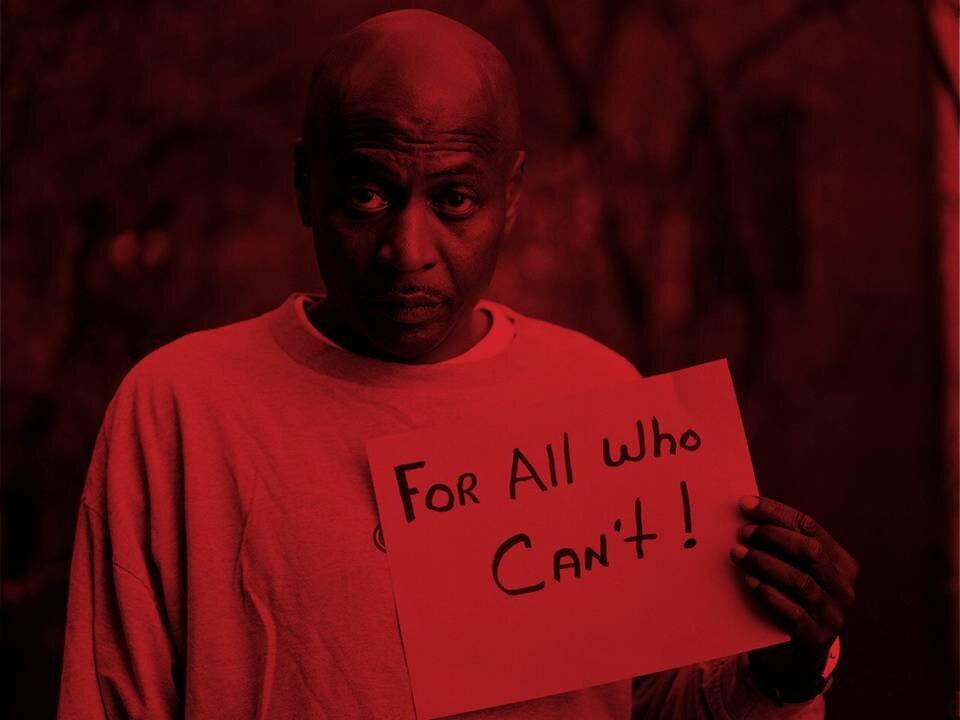

But John pulled courage from inside his pockets of resilience – which he had plenty of – and faced this new setback as the weeks unfolded and the decision and its absoluteness started fading from the media and leaving its indelible mark on criminal law, on history. His lawyer, confidant and friend, did breathe hope through the tiny cell phone, reminding him that the next step was the legislator. And John, pushing RAE to new heights, was in the right position to petition the legislators to write bills, enact laws, debate feverishly for protective measures for the innocent. It wasn’t too late, even after all those years that started back in 1985, to fight. He was good at it.

FOOTNOTE: In 2007, the Legislature approved the Innocence Project Compensation Fund, which allows wrongfully convicted victims to collect a maximum of $ 15,000 for every year spent incarcerated. The total cannot exceed $150,000. John went through the standard and hurdles of red tape in proving that he was “factually innocent”, a stipulation of the Fund that require almost another retrial.

“If I were their family member, if I were their son, would they protest because we’re coming in asking for $150,000?” John said about the initial opposition to the Fund and the resultant difficulty in securing the money. “Maybe it’s because the majority of the people coming in are poor and African American.”

After much wrangling and fierce petitioning, John was awarded $150,000 from the Fund in 2011.

In May of 2011, months after the Supreme Court derailed his dreams and entitlement, John became a Soros Justice Fellow, one of 14 hailing from different states and Washington, D.C. Selected to explore a wide array of issues, including prosecutorial misconduct, federal immigration enforcement, and the harsh treatment of youth, these individuals were chosen by The Open Society Foundations and awarded $1.6 million, divided equally among all 14 for their continued work in the community.

“The passion and vision of the Soros Justice Fellows offer real hope for a fairer, more equitable justice system for everyone in this country,” said Diana Morris, acting executive director of U.S. Programs for the Open Society Foundations. “These extraordinary individuals are working on a wide range of innovative solutions to address the deep flaws in the current system and to restore justice for all.”

SUPREME INJUSTICE: The True Story of John Thompson and His Riveting Journey from Death Row to Freedom